Photo by Futoshi Hanashiro

News14 May 2022

50 years since the Okinawa Reversion - Interview No.1: Director of the Sakima Art Museum

15 May 2022 marks the 50th anniversary of the reversion of Okinawa to Japan. We look back at the past half-century and use interviews with Okinawan people to think from various perspectives about the current situation for Okinawa, which has a different history and culture from mainland Japan.

The first interview is with Michio Sakima, Director of the Sakima Art Museum. In response to a request from the husband and wife Iri and Toshi Maruki, both painters, who wanted to leave to Okinawa their “Battle of Okinawa Pictures” (pictures painted based on testimonies from survivors of the Battle of Okinawa), he persuaded the US military to return a portion of his ancestral lands they had confiscated, and he established an art gallery there. The Sakima Art Museum, established in a location that seems to encroach on a US base, is a good place to think about Okinawa from various angles. We interviewed the Director about the 50th anniversary of the reversion, the US bases problem, and the power of art.

― Please start by introducing yourself.

I was born in 1946 in Kumamoto Prefecture, where my family had been evacuated. It was the year after the Battle of Okinawa, in which a quarter of the population of Okinawa lost their lives. I was brought up in Kumamoto, where my father, a doctor, had opened a clinic, and I went to university in Tokyo. Discrimination and prejudice against Okinawa were still deep-rooted at that time. After graduating, I worked as an acupuncture and moxibustion therapist in Tokyo, but in 1984 came my life-changing meeting with the painters Iri and Toshi Maruki. Ten years after that I established a private art gallery, and now I live in Okinawa.

― Tell us about the 1972 Okinawa reversion and how things were at that time.

I was a student at the time. Seeing it from Tokyo, I was very enthusiastic about the reversion. For Okinawans, I think that the Okinawa reversion was a romantic event like returning to the family home. In the 1951 San Francisco Peace Treaty Okinawa had been split off from the Japanese mainland and handed over to the US as land to be used for military bases. In Okinawa just before the reversion there were lots of slogans along the lines of “like a child brought up by foster parents, we want to return to the warmth of our family home.” Some people expected that once Okinawa Prefecture reverted to Japan, the US military bases there would probably disappear. On the Japanese mainland there was jubilation. I think most people saw it as Japanese territory seized during the war that was being returned as a result of peace negotiations. But Okinawa itself did not see it in that way.

― So from before the reversion there was a difference in attitude between Okinawa and the mainland, was there?

Yes, and it wasn’t just a difference in enthusiasm, but a decisive difference, which still continues today. Nothing has changed since then.

― What sort of changes happened after the reversion?

Okinawa became a tourist destination with over 10 million tourists visiting every year. It is packed with beautiful high-rise tourist hotels. And the scenery changed, with a steady influx of rental Toyotas and luxury cars. But although at first sight Okinawa feels like a modern society, the people of Okinawa Prefecture remained mired in poverty as they had always been.

― Did the US bases problem improve?

No. There was a reduction in bases on the Japanese mainland, but in Okinawa, far from shrinking, they actually increased (when the reversion happened in 1972 Okinawa Prefecture accounted for 58.7% of all the land in Japan used by US military facilities, but this has now increased to around 70%). The situation in which Okinawa is used as a kind of dumping ground for bases continues now, 50 years after the reversion. I think this is clear structural discrimination.

― Why does this situation persist?

It is a US base problem, but it is also a Japanese government problem. The Treaty of Mutual Cooperation and Security between the US and Japan stipulates that Japan will provide bases for the US military. So these could perfectly well be anywhere in Japan. But around 70% of all the land used by the US military in Japan is in Okinawa, which only accounts of 0.6% of Japan’s land area. And because the Japanese people as a whole pretend not to notice this, there is no perception that it’s a problem. When elections are held in Japan, around 80% of people support the US-Japan Security Treaty, but in Okinawa Prefecture 70% oppose it. But since Okinawa Prefecture is 1% of the population, even if everybody in Okinawa opposed the Treaty, this would still only add up to a small number. I think that in the context of Japanese politics, it is extremely difficult to solve the Okinawa bases problem.

Futenma Air Station in Ginowan City, Okinawa Prefecture. Ginowan City in Okinawa is shaped like a doughnut, with the central part of the city taken up by a US military base. The US base occupies over 30% of the city’s land

― The Sakima Art Museum stands in front of the fence of the Futenma US military base, said to be the most dangerous in the world. Please tell me how you came to build the museum.

When I was working in Tokyo as an acupuncture and moxibustion therapist, I met Iri and Toshi Maruki, famous for their “Nuclear Bomb Pictures”*. I was doing some eye treatment for them and became friendly with them, and when they said they would like to put some “Battle of Okinawa Pictures” in Okinawa, I agreed to receive the works. I approached Okinawan galleries and the authorities about putting these works in Okinawa, but no gallery would agree to take them. So then I decided that if galleries and the authorities would not do it, I would build a gallery myself.

* The “Atomic Bomb Pictures” are a series of 15 volumes of paintings based on the actual experiences of those who suffered in the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, by the Hiroshima-born painter Iri Maruki (1901-95) and his wife Toshi Maruki (1912-2000), a Western-style painter and producer of picture books. The couple continued painting these “Atomic Bomb Paintings” for 32 years.

I spent the first three years searching for a site, but I could not find any land that met my conditions. But during my research I discovered that there was around 1800 m2 of my family’s ancestral land inside a US base. The land was inside the fence of the US base, but I couldn’t see any alternative, so I decided to ask the US military to return that land.

― How did you manage to get back part of your ancestral land that was being used for a military base?

First of all I went through the required procedures with the Japanese government to recover the land. But for more than three years I got the same response, that “the US military are unwilling to return it”. I realised that negotiating with the Japanese government wasn’t going to get me anywhere, so I appealed directly to the US military. When I did that, the US military immediately said “A gallery? Sounds good”, and the following year the land was returned. I was absolutely astonished. I had been negotiating with the Japanese government for over three years, but when I spoke to the US military, it only took a single approach. I feel that I saw the reality behind the US-Japan security set-up.

― The different responses between Japan and the US are remarkable, aren’t they?

Yes. I also had the impression that they have different views about art. When the person in charge on the US military side said he would like me to show him the list of works in the (planned?) collection, some of the Japanese people involved gave up hope of the land being returned to me, because I am a collector specialising in war- and peace-related works. But the US military staffer was kind enough to say that a gallery would be an asset to Ginowan City. I had the impression that America has a culture in which art, in the form of works of art, is thought to play an important function in society.

― It took ten years from coming up with the idea for the gallery to opening it. What kept you going?

The power of art. For example, if we try to solve Okinawa’s ridiculous situation, it’s very hard to do this through words or arguments. But I think that art enables understanding by stimulating people’s creative powers. When I was in Tokyo, I had the frustrating experience of complaining about how terrible the Battle of Okinawa* was, and being told “Okinawa wasn’t the only place that suffered terribly”, as people just didn’t get it. But when I saw the Marukis’ work “Battle of Okinawa Pictures”, I was determined that people should see these pictures, as they contained the whole story, and this gave me great strength. I got that strength from the painters Iri and Toshiki Maruki.

*The Battle of Okinawa consisted of fierce fighting between the Japanese and US militaries between late March and late June 1945, mostly on the main island of Okinawa. This fierce land battle also embroiled local residents, and more than 200,000 were killed. An estimated 200,000 tonnes of ammunition were used in Okinawa.

― Once you opened the museum, what sort of people visited it?

Middle and high school students visiting Okinawa on study trips and the like as part of peace studies. Pupils learn the history of the Battle of Okinawa (March-June 1945) in class at school. They visit “Gama” (“Gama” is an Okinawan dialect word for the natural caves into which part of the population escaped and in which they were driven to commit suicide), and have it explained to them that tragic things happened there. Most middle and high school students are affected by what they see, but it is not easy to see the overall picture. In that case, if they stand in front of the “Battle of Okinawa Pictures”, what they have studied and what they have felt visiting the scene all fall into place.

― Have there been any particularly memorable occasions?

The event that moved me most was the influence we had on the life of a 17-year-old girl. She wrote that “right up to today, I was only thinking about dying. But I have the feeling I can carry on living from tomorrow”. The works depict extreme war situations, so at first sight they are shocking, but that girl gained hope and courage from them.

― The works really bring the situation home, don’t they?

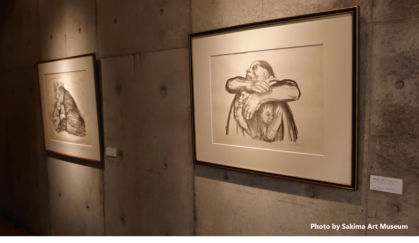

I was talking just now about the Battle of Okinawa, but in the current Ukraine war, you can see on the TV news every day images of young mothers pulling their children along by the hand as they flee, and this is exactly like the Battle of Okinawa. In Okinawa today the memories and trauma of the war are still present and permeate the atmosphere, just like the situation in Ukraine. When Ukraine was invaded, as a message from the gallery, we displayed three works by the German sculptor Käthe Kolwitz* (1867-1945, who produced works filled with sympathy for mothers, children and the weak harmed by war). Because of what’s happening in Ukraine, the world is grieving, isn’t it? But I think that people who stand in front of Käthe’s works are able to understand what is happening in the world today.

― What do you think the power of art is?

Art has the power to create images. These take us at a stroke beyond political bipartisanship and competing interests, and reach the real heart and wishes that humans have inside them. I think that in order to feel something unrelated to oneself as if it were one’s own issue, the power to imagine it is neccessary. To change a difficult situation we first need to change ourselves. I want to continue to create a gallery that uses art to think about the true nature of humanity.

(Interviewer: Nana Ota, English translation: Jason James)