News

News29 September 2022

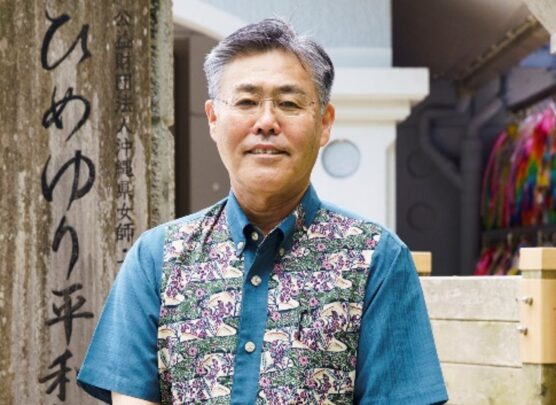

50 years since the Okinawa Reversion - Interview No. 2: Chо̄kei Futenma, Director of the Himeyuri Peace Museum

This year marks 50 years since the reversion of Okinawa to Japan. We look back at the past half-century and use interviews with Okinawan people to consider from various perspectives the current situation in Okinawa, whose history and culture are different from mainland Japan. The second interview is with Chо̄kei Futenma, Director of the Himeyuri Peace Museum. Mr. Futenma started working for the museum when it opened in 1989, and was appointed Director in 2018, becoming the first Director to be born after the War. We asked him about the Battle of Okinawa and his efforts to ensure it is not forgotten, from the opening of the museum up to the present, and continuing into the future.

- Would you please tell us about the Battle of Okinawa and the Himeyuri Student Corps?

In March 1945, during the final phase of the Asia-Pacific War, the Japanese and US armies fought a ground war in Okinawa that embroiled the local population. The Himeyuri Student Corps, consisting of 222 female students from the Okinawa Shihan Women’s School and the Okinawa Daiichi Women’s High School, commanded by 18 teachers, totalling 240 people, was deployed on the night of 23 March 1945 to work as nursing staff at the Okinawa Army Hospital (also known as the Haebaru Army Hospital). The Himeyuri Student Corps were split up and worked in the dug-outs, mostly helping to nurse and treat wounded soldiers. They found themselves working day and night as nurses, with hardly any time to sleep. This was heroic work for female students still in their teens, but they continued to work in the dug-outs, even when they were struggling to get hold of a single rice ball a day to eat.

Ruins of the Okinawa Army Hospital to which the Himeyuri Student Corps was deployed

Pressed by the US army, they subsequently withdrew to the southern tip of the main island of Okinawa. Then on the night of 18th June 1945, the students at the Army Hospital received the order to dissolve the unit. They were told that, from now on, they had to make their own decisions and leave the dug-outs. With the US army almost on top of them, the students were turned out of the dug-outs and fled, amidst a hail of shells. The students had been indoctrinated with the idea that it was shameful to be taken prisoner by the Americans, so in their fear of being taken captive, they lost their lives wandering around the battlefield in southern Okinawa, near the coast. Within just a few days of the dissolution order, over 100 of the Himeyuri Student Corps were killed.

- So they were really determined not to be captured?

The students at that time thought that they must at all costs avoid being captured. They believed what the troops had told them, which was that women captured by American soldiers would be raped and mercilessly killed. In terror of this, the students fled all over the battlefield, and many lost their lives who could have been saved if they had been quickly captured by the US army. Those who survived, on the other hand, did not speak about their wartime experiences for a long time, plagued by the thought that they had survived while their schoolfriends had died. In fact, the Battle of Okinawa was not spoken about in Okinawa for a long time.

- Why was it not spoken about?

Many people have the impression that the Battle of Okinawa is often talked about in Okinawa, but most people actually did not speak about their experiences to their families. A family is in some sense a place of relaxation, so to go out of their way to talk about those hard experiences – unless their children or grandchildren strongly wanted to hear about them, perhaps they couldn’t talk about those cruel experiences. Most of the Himeyuri survivors did not talk to their children about it.

- How did you yourself first learn about the Battle of Okinawa?

I think that people of my generation first learnt of the Battle of Okinawa after quite a long time had passed and we had grown up. One of the courses I took at university involved reading a book about the Battle of Okinawa every week, and this was the first time I came across it.

I was a middle-school student in 1972 when Okinawa reverted to Japan, and at that time the Battle of Okinawa was not taught about in schools. There was great public interest in those days in the push to have Okinawa returned to Japan, and there was a spate of incidents and crimes by people connected with the US military bases, so people were mainly interested in human rights issues resulting from the US bases in Okinawa.

But in the late 1970s and the 1980s, there was controversy about the displays at the Okinawa Prefectural Peace Memorial Museum, as well as about the fact that statements that civilians had been killed by the Japanese military were expunged from textbooks about the Battle of Okinawa. There was a groundswell of opinion that the record should be set straight about the Battle of Okinawa. At the same time, there were an increasing number of school field trips to Okinawa, and pupils started to be taught about peace education and the Battle of Okinawa. So from the late ’70s there started to be a feeling that it was important for people to hear about the Battle of Okinawa. So it isn’t the case that the Battle of Okinawa has long been taught in educational settings, but I think that social movements and trends played an important role in triggering the teaching of it.

- What was the background to the opening of the Himeyuri Peace Museum?

In the late ’70s, the Himeyuri alumnae groups, consisting of survivors of the former Himeyuri Student Corps and alumnae of the two schools, considered rebuilding the schools, which had been destroyed in the Battle of Okinawa, but they couldn’t raise the necessary funds, so they had to give up the idea. But when nearly 40 years had passed since the War, the former members of the Himeyuri Student Corps were concerned that people were increasingly forgetting about the Battle of Okinawa, so they decided to build the Peace Museum to pass on information about what they had actually experienced during the War. The alumnae groups worked together to raise the necessary funds for the construction, while the surviving members of the Himeyuri Student Corps were in charge of the displays.

The survivors went back for the first time in 40 years into the dugouts they had occupied at the time of the Battle of Okinawa, dug up and collected mementos and human bones left there, and exchanged their testimonies with each other. Items collected from the dug-outs, like their classmates’ pencil cases and rigid plastic sheets to rest writing paper on, are on display at the museum. I have heard that when items like these pencil cases and plastic sheets emerged from the mud, the former members of the Himeyuri Student Corps wept as they picked them up, saying that these important items belonging to their friends had remained buried for 40 years, and that they should have gone to look for them earlier. I think this was the driving force behind their continued activities after the museum opened.

The Himeyuri Peace Museum opened on 23 June 1989, 44 years from the day on which organised hostilities ended on Okinawa.

- What kind of activities have there been since the museum opened?

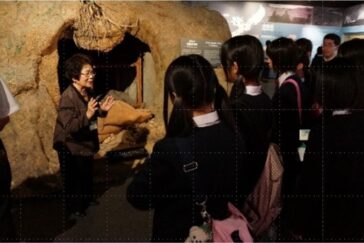

The former members of the Himeyuri Student Corps became “testifiers” once the museum opened. They gave explanations and talks in the galleries to pass on their personal experiences of the War. Many of the survivors of the Himeyuri Student Corps were working as teachers after the War, so they were used to speaking in public, but this doesn’t mean that it was straightforward for them to talk about their experiences at the beginning. When they spoke of their classmates, their chests would tighten and they would become unable to speak, or they would start weeping. But the serious expressions on the faces of visitors to the museum, and the sympathy they received, were a big encouragement to them, so they began to feel the value of talking about their experiences. They were motivated by a feeling that they must pass on accurate information to future generations, and they have managed to continue giving their testimonies for nearly 30 years. Also, together with the curators, they have been active in passing on information about the Battle of Okinawa and the wartime experiences of the the Himeyuri through special exhibitions and events.

A former member of the Himeyuri Student Corps testifying to museum visitors

- How will this be continued in the next generation?

By around the year 2000, the Himeyuri Student Corps members were nearly 80 years old. They started thinking about the future and how the museum could pass on their experiences once they were no longer alive. Many of the testifiers at that time felt that it would be hard for people who had not experienced the war to explain those experiences.

My own knowledge of the Battle of Okinawa became much more accurate through showing exhibits with the Himeyuri Student Corps. So I gradually came to think that we must find a way of passing on their stories. But when I was confronted with the gravity, the intensity, of what they said, I sometimes thought this would be impossible for me. So I went with six of the testifiers to see what was happening in Europe (the Auschwitz-Birkenau Museum, Anne Frank House etc.), where the change-over to a new generation of speakers was happening faster than it was here.

- What did you think of the Auschwitz-Birkenau Museum?

I was impressed to see people who had not experienced the War doing a great job getting the message across, and this emboldened me. Takeshi Nakatani, the only Asian guide at the Auschwitz Museum, talks simply and neutrally about what happened, but you still get a strong sense of atmosphere from actually being there at Auschwitz. This experience taught me the importance of training people to tell the stories, and it is linked to our subsequent activities at the museum.

Takeshi Nakatani, the only Asian guide at the Auschwitz Museum

- What were your feelings in 2018 on becoming the first Director of the Museum born after the War?

My predecessor Yoshiko Shimabukuro was Director for around seven years. I supported her throughout that time, and when I saw the power of her testimony first-hand, I felt that there was no way I could take on such an important responsibility. But both the Director and the other testifiers were nearly 90, so we couldn’t ask them to keep on doing it. It is not just me who has taken on their work and their activities, but our staff were all born after the War too, and we all feel the same way about taking this on.

When we revamped the museum for the second time in 2021, for the first time people who had been born in the postwar period accounted for a majority of the staff, so we put together an exhibition on the theme “Explaining to a generation even further removed from War”. As people who had not experienced the War, we thought about how best to get the message across to the generation born after the War, and we went through a process of trial and error.

The exhibition space after the 2021 revamp

- The museum has now been open for 33 years.

In 1989 when the Himeyuri Peace Museum opened, it was exactly the year that the Cold War came to an end with the collapse of the Soviet Union. In November that year the Berlin Wall, which had separated East and West Germany, came down, and there was a chance to build a peaceful world for the future. But war and conflict has continued unabated after that, with terrorism as well, and there is a growing sense of crisis as regards the situation in Asia too. I feel that we need to carry on giving our testimonies, to urge how terrible war is and how important peace is.

- How do you think the Museum should change in the future?

There has been no change since we opened in the message we need to get across. How tragic and cruel war is, and how precious life is. But some aspects of getting this message across are difficult with the change in generations, so our function is to think about how we can get this across to a new generation. The issue for us in the future is how to get the younger generation to see war and think about war as something relevant to themselves. I would also like to strengthen our international network and experiment with connecting our activities with interested parties outside Okinawa.

Entrance of the Himeyuri Peace Museum (L) and Himeyuri Memorial

About the Himeyuri Student Corps

- In March 1945 18 teachers and 222 students were mobilised for the Battle of Okinawa, of whom 136 died (13 teachers and 123 students).

- 30 former members of the Himeyuri Peace Corps became ‘testifiers’, involved with the construction of, and managing the activities of, the Peace Museum.

- As at August 2022, there were 4 testifiers (all over 90).

(Interviewer: Nana Ota, English translation: Jason James)